Structural Violence: The role of poverty, trauma and stress in mental health and addictions

Photo Credit: Unsplash User G. Crescoli

In the Canadian Mental Health Association (CHMA) video on Structural Violence: The role of poverty, trauma and stress in mental health and addictions, Jenny Morgan speaks from her position as Director of Indigenous Health at BC Women’s and Children's Hospital to explore ways socioeconomic inequities impact health and demonstrate how health authorities and organizations can be accountable for the delivery of trauma-informed and culturally-safe care. Vanessa Brcic then shares her perspective as a family doctor who specializes in vulnerable patients, delving into how the body responds to chronic stress and why patient-centered, integrated care that addresses basic needs is the most effective medical intervention. Jenny is the Director, Indigenous Health, at BC Women’s & Children’s Hospitals, and a sessional instructor at the UBC School of Social Work. Vanessa is a family physician, a registered therapeutic counsellor, and a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Family Practice, UBC.

The presentation opens with a discussion of what we know about the connections of substance use and experience of trauma: “The inter-relationships of trauma/violence, mental illness and substance use in women have been described by researchers as “profound” and “staggering”. As many as two-thirds of women with substance use problems report a concurrent mental health problem (e.g. PTSD, anxiety, depression) and the also commonly report surviving physical and sexual abuse either as children or adults.”

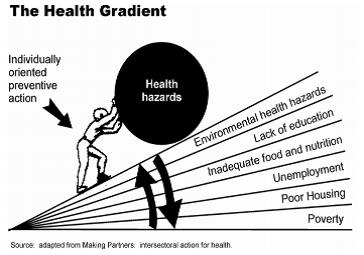

They look at Social Determinants of Health opportunities for intervention at 3 levels: individual, health, and environment, and support for the “chronic stress response”.

The presenters discuss the roots of structural inequities (“structural violence”) and note: “people impacted by social inequities often experience multiple forms of violence; structural conditions increase the risk of interpersonal violence, and of experiencing challenges in accessing supports to improve physical and emotional safety.” They look at Trauma and Violence-Informed Care (TVIC) as a means of addressing structural violence. This method locates trauma as an outcome of the structural violence rather than within the psyche of the individual. It is not a form of therapy, but rather a general harm-reduction approach that “prioritizes the need to create an emotionally safe environment based on an understanding of the health effects of trauma” and the compounding effects of interpersonal and structural forms of violence (e.g. poverty, racism). A TVIC approach aims to engage “staff and organizational policies to deliver care that responds to inequities, is tailored to the context of a person’s life, and creates safety through cultural competence”.

The presenters state that there is commitment within the BC Health community to create a safe and equitable system that builds cultural competency and equitable and culturally safe providers and organizations in supporting Aboriginal patients. They give examples of how organizations can model non-stigmatizing language in a variety of ways, from signage to EMR systems to how clients’ situations are discussed by staff.

The presentation looks at the mechanisms of chronic stress, noting that “the brain is like Velcro for the bad and Teflon for the good”. Both traumatic experiences and ongoing ‘toxic’ stress can be overwhelming, perpetuating the chronic stress response where people get stuck in reactive/survival mode, and creating an obstacle to forming everyday human connections and to making long-term plans. The amygdala sends alarm messages to the hypothalamus that initiate release of stress hormones (cortisol, adrenaline, NE) and trigger the fight/flight/freeze response. The emotional reactions in this response come from implicit memory and are not accessible by the executive centers of the brain, and leave the person with a chronic stress/fear pattern ready to be awakened by any trigger.

The presenters note that Aboriginal peoples, who, as a group, have had to endure trauma, and at the same time have been deprived of the tools of resiliency (beliefs, rituals and institutions) which help traumatized societies to reconstruct their identity, have significant vulnerability to trauma-induced chronic stress.

The recommendations made are to treat trauma as a determinant of health in clinical situations by:

1. Safety First – provide safety as a top priority:

a. Counter physiological overwhelm

b. Validate, actively build the relationship

c. Find opportunities for choice/control, and identify strengths (notice not only vulnerability)

d. “Resist the righting reflex”

e. Work with boundaries, preferences and choice around health care decisions and visits

2. Normalize – normalize emotions and symptoms:

a. Present-time experiences may be associated with the past; refocus on present time (notice safety)

b. Implicit memories involve hypo- or hyper-arousal: helplessness, shame/depression/freeze; or fear/rage/anger/anxiety (all of these are survival responses)

c. Expect decreased capacity to integrate/modulate physiological responses, limited communication and executive function (listen first and set simple goals)

3. Anticipate Feelings of Threat – expect that health care will feel like an unsafe space

a. Institutional and colonial history; ongoing discrimination

b. Illness involves uncertainty, vulnerability, navigating a maze of services, new relationships and environments

c. A sense of ongoing threat and lack of safety is a normal response to trauma

d. Work in the present time

4. Directly address SDOH & structural violence

a. Individuals can’t separate past experiences of stress and overwhelm from present experiences

b. Stressful, overwhelming experiences are cumulative

c. Recognize that the problem is the environment, not the person – help create greater safety in the environment and find strengths in the person

d. Develop action plans in clinical visits to increase safety and supports